Part One: 1965-2019

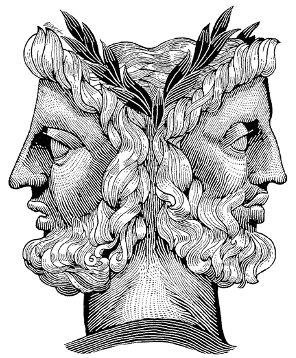

Janus is the name of the Roman god of gates and transitions. We are most familiar with the two-facing god each year in the month named after him- January. Each year we follow a tradition of looking back at the year just completed and ahead to the one that is upcoming. Although we are now in August, no time could be more appropriate for me to look backward and forward at the healthcare supply chain than now- August, 2020.

If my life were a month, I would probably be early or late November. On the 8th of that month I will turn 75 and will be celebrating fifty-five years in healthcare, forty-eight of which have been associated with the supply chain. For me the road behind me is far longer than the one ahead, but what the hell, let’s take a look- in both directions.

This month’s blogs will address the following subjects:

Looking Back- 1965. I entered the world of healthcare in August of 1965 when I entered U. S. Navy Hospital Corps School at the Great Lakes Naval Training Center in North Chicago, Illinois. A year later, I was in the jungles of Vietnam serving as a marine medic.

When I began, there were over 7,500 hospitals in the U. S. and while the Social Security Act of 1965 had been passed, it was yet to have been enacted. Medicare, the primary component of the act, had yet to be implemented.

The system that was in place was a “Sick Care” system- one in which people waited until they developed symptoms, then called their general practitioner for an appointment. If they needed care, the doctor would probably admit them to their local not-for-profit community hospital. Once admitted, they stayed as long as it took to get them better. Revenue came from three sources: (1) uninsured self-pay, (2) self-funded private insurance and (3) employer-funded insurance. Reimbursement was based on a “cost-plus” model in which hospitals added a percentage to the cost of doing business- supplies, etc.

The healthcare supply chain in 1965 had no name. While there were Purchasing Departments, Sterile Processing Departments, Linen Departments, etc. there was very little consideration given to the thought of an integrated, interdependent function. While some regional purchasing groups existed, the large Group Purchasing Organizations (GPOs) that we know today either did not exist or were in their nascence. Supply management consisted largely of multiple pint of use storage areas stocked by floor staff. Paper orders were sent to the warehouse, where they were filled, taken to the nursing floor and dropped off. Staff put products away. “Logistics” was a term that applied to the military- the movement of troops, equipment and supplies. American Hospital Supply was the only national distributor, with local and regional distributors serving the rest of the country. The state of the healthcare “supply chain” was this: People ordered stuff; people waited for stuff; people put stuff away, and repeated the process as often as needed.

1966-1982. By 1982, many changes had taken place in healthcare supply chain management. While the basic care model (Sick Care) remained in place, an organized, systematized approach began to enter the field. The professional term for the discipline was “Materials (or Materiel) Management.” Purchasing, Internal Distribution, Sterile Processing and often Linen Distribution, Mail and Messenger Services were combined under a single leader- The Director of Materials. While the disciplines rose in importance to achieve department director status, they were yet to reach C-suite levels. Emphasis was on inventory management. Low unit of measure partnerships were pioneered. Exchange cart systems were put in place to control inventory levels and assure that patient charges were processed. The GPOs were beginning to gain in importance. Many elements of the system remained. Not for profit community hospitals competed for market share across the country. Supplies were generally purchased through distributors such as American Hospital Supply and the newly emerging national forces such as Owens and Minor and Medline. With its inception in 1966, Medicare became a primary source of revenue, creating boom times for many hospitals. For-profit chains such as the Hospital Corporation of America began to emerge as a potential threat to community hospitals.

1983-2000: During this period, several game-changing events took place in healthcare that significantly increased the importance of the Supply Chain. The first of these was the passing of the Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act (TEFRA), which changed the way in which Medicare reimbursed for care. Prior to TEFRA, Medicare reimbursed on a cost-plus basis. There was very little oversight and even less of an incentive to control costs. Costs were, in effect, passed on to the patient, the government (Medicare) and the insurance companies. In many ways, Medicare had given healthcare organizations the ability to print money. All that was soon to change TEFRA introduced Diagnosis Related Groupings (DRGs) and the concept of prospective reimbursement. The DRGs broke down procedures by categories, assigned procedures specific numbers and used the newly-evolving national data bases to determine an average cost for treating each DRG. Medicare would pay the amount it determined appropriate for a DRG prospectively. If a hospital could provide the service for less than the reimbursement, it made money. If it couldn’t, it lost money. Suddenly, cost management became a matter of survival. Concurrently another big development shocked the healthcare community. Hospital Corporation of America, the nation’s largest for profit system, proposed a merger with American Hospital Supply, the nation’s largest distributor- one who owned the largest and most advanced data base of supply activity and spending history in the country. The prospect of a merger of those organizations struck fear in the hearts of the not for profit community. With the changes in reimbursement coupled with the data advantages the merged company could bring to bear on the market, how could they possibly survive?

The answer to this question revealed itself in the rise of the national GPOs- Premier, AmHS, VHA, UHC, Amerinet, Broadlane and MedAssets, and HealthTrust Purchasing. Organizations turned to the GPOs to “get prices down”. The GPOs rise in power became the primary weapon against controlling supply costs. Coupled to this was the rise in professionalism among supply chain leaders. More and more were Masters-prepared, and more and more often, healthcare looked outside of itself for direction on how the supply chain should work, including the seminal study in 1996, The Efficient Consumer Healthcare Response. Using the food industry as a model, the study became the first graphic representation of the healthcare supply chain activity. It developed a roadmap toward the future and introduced supply chain management concepts and processes common to industry but heretofore seldom used in healthcare on a day to day basis.

2000-2019: The last twenty years has seen a distinct rise in the professionalization of the healthcare supply chain. It has also seen (1) the rise of super Integrated Delivery Networks (IDNs), with many, many decentralized non-acute satellites, (2) the digitization of the world, which has provided endless streams of relevant, operational data that can be turned into measurable strategies, (3) the continued “industrialization” and “professionalization” of the healthcare supply chain.

With the growth of IDNs and the impending disappearance of the stand-alone community not-for-profit hospital, the look of healthcare in a typical community has changed drastically, as have the challenges to the supply chain. Let’s look at my community as an example.

I first came to Northeast Ohio in 1983, as Associate Director, Materials Management at Timken Mercy Medical Center in Canton. It was a member of a loosely affiliated system under the Sisters of Charity of St. Augustine, whose headquarters were located in Richfield. The System included TMMC, three hospitals in and around Cleveland and a hospital inm South Carolina. While technically a part of a system, each hospital acted independently as not for profit community hospitals. In Canton, TMMC and Aultman Hospital competed for the business. There were two community hospitals in Massillon as well. Akron was ruled by Akron General and Akron City Hospitals and Cleveland was dominated by University Hospitals, The Cleveland Clinic Foundation and MetroHealth Medical Center, with the three CSA hospitals lagging behind and several other stand-alone community hospitals serving the suburbs. Over the years, IDNs were formed, merged or acquired smaller hospitals, failed and were acquired by the giants. Today, the Northeast Ohio healthcare landscape is dominated by The Cleveland Clinic and University Hospitals, with MetroHealth holding on due to its critical mission to the underserved. Every place that was in business when I moved to Canton in 1983 is either (1) belly up, (2) part of the Clinic or MetroHealth, or (3) affiliated with Wm. Beaumont in Detroit! The single remaining stand-alone not-for-profit community system not affiliated with the big guys is Aultman.

Those changes brought with them the need to pay more attention to supply chain operations. Logistics- formerly left to the big or regional distributors, suddenly became important, as systems’ footprints spread out instead of up. Many supply chain leaders began to realize that they had neither the resources nor the training to deal with these challenges, and they began to employ organizations such as St. Onge to help them address issues that heretofore had gone without attention.

Consideration was given to tactics such as self-contracting, self-distribution and the building of Consolidated Services Centers- places in which demand could be aggregated for warehousing, linen processing, instrument sterilization and preparation as well as pharmaceutical dosing could be done more effectively and possibly at a lower cost.

Those that tried to do things on their own often trained their staff in Lean methodologies, formed Low Unit of Measure distribution relationships with the major distributors and brought in “fee” or low-cost resources from their GPOs in an effort to keep operational costs down in an industry where even the best performers often had operating margins below 5%.

Over the fifty-four years from 1965 to 2019, the healthcare supply chain has witnessed itself go from a process without a formal name to one that had begun to utilize the tools of industrial engineering and the methodologies employed by other industries to maximize the effectiveness of their operations.

Things were looking up.

Then came 2020.

Like this article? Subscribe to our blogs: